ARPA-E might be my favorite obscure government agency.

One of the best parts of my job is getting to meet with smart people who are thinking about big problems. I haven’t had as many opportunities to meet with big groups over the last year because of the pandemic, but I recently hosted a cohort of graduate students for a virtual discussion that helped make up for lost time. Our conversation served as the inaugural session of what I’m calling Gates Notes Deep Dive—a new series that brings together diverse groups of people from around the country to explore one topic in depth.

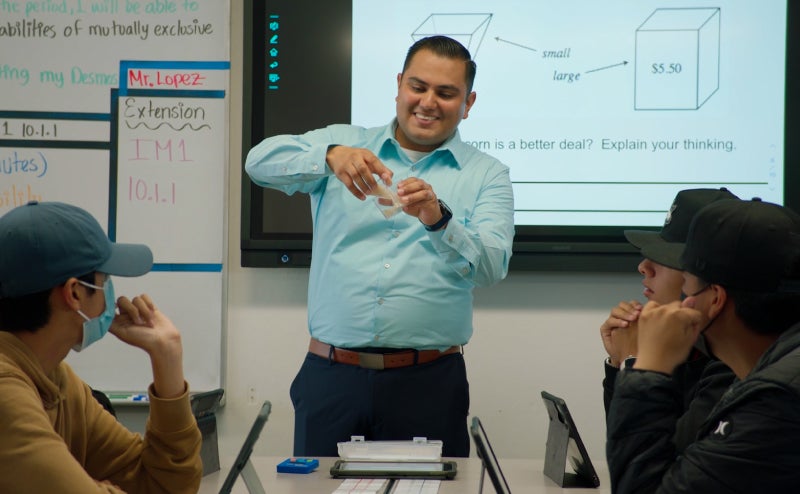

Our subject this time was how data can help improve educational outcomes for Black and Latino students and students from low-income backgrounds. All of the participants are studying either education or public policy, and each one was hand-picked by their university to take part in our discussion. We were also joined by a couple of experts who are already working on education data initiatives.

Our foundation—like most organizations—relies on data to make decisions. In global health, we helped create a group called the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation to make data easier to access and study. (You might have seen their COVID-19 models in the news over the last year.) For example, researchers are able to look at the causes of childhood deaths around the world and see which specific pathogens are responsible in which areas. That information is incredibly useful when you’re deciding where to invest funding.

Unfortunately, that level of granularity doesn’t exist when it comes to studying education. We know more about why young children die than why older ones drop out of school. Part of the problem is that the objectives are somewhat less clear when it comes to education. With global health, the goal is obvious: you want kids to survive and thrive into adulthood. With education, there isn’t broad consensus on what the targets should be. Is the goal for all students to graduate? To get a good job after college? To be thoughtful, well-rounded adults?

As a result, education data here in the United States is often incomplete, incompatible, or difficult to use. It doesn’t always focus on the most important outcomes or the students who are most likely to be left behind (like Black and Latino students and students from low-income backgrounds).

In an ideal world, students and parents could use data to make decisions about their future. Educators would be able to look at each student individually, see where they’re falling behind, and connect them with resources to help them catch up. Policymakers—especially state governments—could identify which areas need more investment while protecting students’ privacy, and organizations like our foundation could bring everyone together to learn from the highest performing schools.

The good news is that there are a number of promising new efforts to collect and organize better data. Deep Dive participants got to hear from four of them. Each of the new tools and systems we looked at was really impressive, giving a much clearer view of opportunities to make the education system work better for everyone. Each of the presenters is doing an amazing job making more data available to more people, and our foundation looks forward to continuing to support them.

One of those tools is SeekUT, a database created by the University of Texas system. SeekUT is all about helping students understand the value of a degree and make decisions about what to study. It uses census data to show not only what you can expect to earn with a particular degree but how that changes over time and how much loan debt you might owe. For example, five years after graduation, a biology major at UT El Paso can expect to make an annual salary of $48,000 and pay $175 a month in loans.

Choosing what to study in college is, of course, about more than just how much money you’ll make. You also want to pick something you’re interested in. Initiatives like SeekUT are simply trying to empower students to make more informed choices. You can’t make the best decision for you and your economic situation without all the information.

It was thrilling to not only see a demonstration of some of the early tools emerging to help students, teachers, and policymakers, but also to engage in a dialogue with the young people who are moving this work forward. Some of the Deep Dive participants were teachers themselves, which was great to see. Teachers need to be at the forefront of this movement to shape the data in a way that’s actually useful for them.

The graduate students I met with will lead the way in designing and deploying new tools. They asked great questions—including how we combat bias in data collection and how the role of education will evolve in the decades to come—and I know all of them have brilliant ideas for how to address inequities in our country’s education system. Future leaders like them make me optimistic that brighter days are ahead for America’s students and teachers. I’m looking forward to hosting more Deep Dive sessions on other topics.