When you see good things happening, you can channel your energy into driving even more progress.

I’ve spent a lot of time over the last month talking about climate change. Whether it’s on my book tour, in media interviews, or just during conversations with colleagues, it’s been great to have so many thoughtful conversations with people about how we prevent the worst effects of climate change.

Most of the questions I’ve gotten are about how we get to zero greenhouse gas emissions. Mitigation is the biggest climate problem we need to solve, and it’s been great to see it get so much attention. But I’ve noticed there’s one key topic that people don’t ask about as much: how we can help the world adapt to climate change.

I understand why. I dedicated five chapters of the book to mitigation and only one to adaptation. (In retrospect, I wish I had written more about the subject.) But there’s a reason I named my book “How to Avoid a Climate Disaster” and not “How to Stop Climate Change:” Our climate is already changing.

You just need to look at last month’s freeze in Texas and last year’s wildfires in California to see that extreme weather events are becoming more common. The scary thing is that these events aren’t the only (or even the most devastating) way a warming world is making life more difficult for people. The biggest damage is happening too gradually to make headline news, mostly in places near the Equator—and no one is more at risk than the world’s poorest people.

About two-thirds of those living in poverty work in agriculture, often relying on the food they grow to feed their families. A warmer world will be problematic for relatively well-off farmers in America and Europe, but potentially deadly for low-income farmers in Africa and Asia.

The closer you live to the Equator, the worse the effects of climate change will be. Droughts and floods will become more frequent, wiping out harvests more often. Livestock will eat less and produce less meat and milk. The air and soil start to lose moisture, leaving less water available for plants; in South Asia and sub-Saharan Africa, tens of millions of acres of farmland will become substantially drier.

When you’re already living on the edge, any one of these changes could be disastrous. We’re likely going to see a situation for these farmers where, instead of your crop getting wiped out every ten years, it gets wiped out every four years. If you don’t have money saved up to buy imported food—which is the case for most smallholder farmers—your children will likely become malnourished and more susceptible to disease.

The worst impact of climate change in poor countries will be to make health worse—which is yet another reason why we need to help the poorest improve their health. This starts with raising the odds that malnourished children will survive by improving primary healthcare systems, doubling down on malaria prevention, and continuing to provide vaccines for conditions like diarrhea and pneumonia. We also need to ensure that fewer children are malnourished in the first place by helping poor farmers grow more food.

“We need better methods and tools to grow food, just like we need to find zero-carbon ways to move around and generate electricity.”

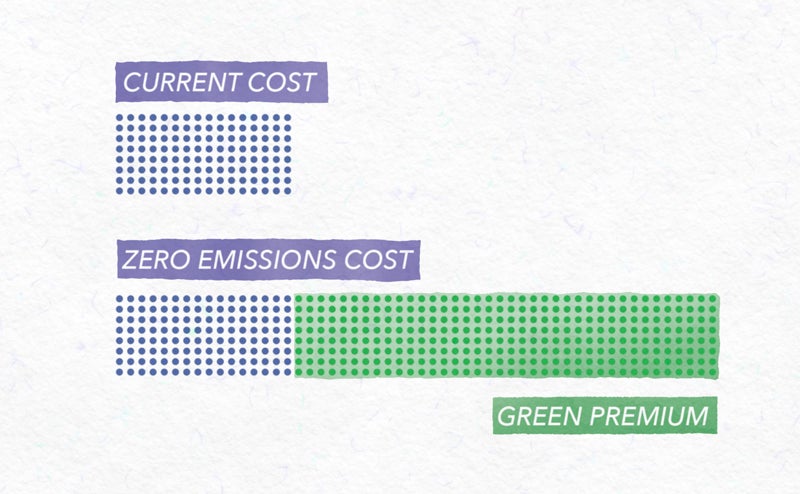

This is a problem we can help solve with innovation. We need better methods and tools to grow food, just like we need to find zero-carbon ways to move around and generate electricity. No other organization is in a better position to create the innovations that will help poor farmers adapt to climate change in the years ahead than CGIAR, a global partnership that helps make plants and animals more resilient and productive. (I’ve written about how amazing CGIAR is before.)

Our foundation first got involved with CGIAR more than a decade ago, when we supported their work to develop drought- and flood-tolerant varieties of staple crops like maize. We’re already seeing big improvements in places like Zimbabwe. Farmers in drought-stricken areas there who used drought-tolerant maize were able to harvest up to 500 more pounds per acre than farmers who used conventional varieties—producing enough to feed a family of six for nine months.

CGIAR and other organizations are also creating tools to help farmers adapt to unpredictable weather, like sensors that tell you when to plant seeds and phone apps that help identify pests. Poor farmers need more advances like these, but to provide them, we need to invest more money in agricultural R&D. Doubling CGIAR’s funding so it can reach more farmers is one of the main recommendations by the Global Commission on Adaptation, which I led along with former UN secretary-general Ban Ki-moon and former World Bank CEO Kristalina Georgieva. (Other recommendations include shoring up water infrastructure and building a stronger safety net to help farmers recover faster.)

If we don’t take steps now to help farmers adapt, we’re setting ourselves up for a humanitarian and geopolitical disaster. The U.S. military predicts that climate change will become a huge driver of global instability. When people can’t grow enough food to feed themselves, they often leave those areas for places that can better support their families. We’re going to see more “climate refugees” move to cooler regions as the world gets warmer. The Department of Defense is already thinking about where a warmer climate could cause conflicts that they would be asked to intervene in.

It’s deeply unfair that the people who contribute the least to climate change will suffer the worst from its effects. Extreme poverty has plummeted in the past quarter century, from 36 percent of the world’s population in 1990 to 10 percent in 2015 (although COVID-19 is a huge setback that is undoing a great deal of progress). Climate change could erase even more of these gains, increasing the number of people living in extreme poverty by 13 percent.

Rich and middle-income countries are causing the vast majority of climate change, and we need to be the ones to step up and invest more in adaptation. The world’s poorest deserve our help, and they need more of it than they’re getting.