What gives our lives meaning? And what if one day, whatever gives us meaning went away—what would we do then?

I’m still thinking about those weighty questions after finishing Homo Deus, the provocative new book by Yuval Noah Harari.

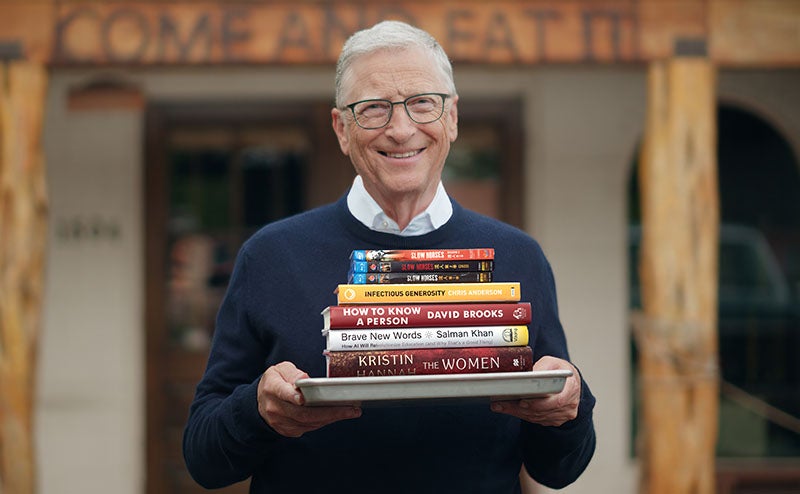

Melinda and I loved Harari’s previous book, Sapiens, which tries to explain how our species came to dominate the Earth. It sparked conversations over our dinner table for weeks after we both read it. So when Homo Deus came out earlier this year, I grabbed a copy and made sure to take it on our most recent vacation.

I’m glad I did. Harari’s new book is as challenging and readable as Sapiens. Rather than looking back, as does, it looks to the future. I don’t agree with everything the author has to say, but he has written a thoughtful look at what may be in store for humanity.

Homo Deus argues that the principles that have organized society will undergo a huge shift in the 21st century, with major consequences for life as we know it. So far, the things that have shaped society—what we measure ourselves by—have been some combination of religious rules about how to live a good life, and more earthly goals like getting rid of sickness, hunger, and war. We have organized to meet basic human needs: being happy, healthy, and in control of the environment around us. Taking these goals to their logical conclusion, Harari says humans are striving for “bliss, immortality, and divinity.”

What would the world be like if we actually achieved those things? This is not entirely idle speculation. War and violence are at historical lows and still declining. Advances in science and technology will help people live much longer and go a long way toward ending disease and hunger.

Here is Harari’s most provocative idea: As good as it sounds, achieving the dream of bliss, immortality, and divinity could be bad news for the human race. He foresees a potential future where a small number of elites upgrade themselves through biotechnology and genetic engineering, leaving the masses behind and creating the godlike species of the book’s title; where artificial intelligence “knows us better than we know ourselves”; and where these godlike elites and super-intelligent robots consider the rest of humanity to be superfluous.

Harari does a great job of showing how we might arrive at this grim future. But I am more optimistic than he is that this future is not pre-ordained.

He argues that humanity’s progress toward bliss, immortality, and divinity is bound to be unequal—some people will leap ahead, while many more are left behind. I agree that, as innovation accelerates, it doesn’t automatically benefit everyone. The private market in particular serves the needs of people with money and, left to its own devices, often misses the needs of the poor. But we can work to close that gap and reduce the time it takes for innovation to spread. For example, it used to take decades for lifesaving vaccines developed in the rich world to reach the poor. Now—thanks to efforts by pharmaceutical companies, foundations, and governments—there are cases where that lag time is less than a year. We should try to narrow the gap even more, but the larger point is clear: Inequity is not inevitable.

In addition, in my view, the robots-take-over scenario is not the most interesting one to think about. It is true that as artificial intelligence gets more powerful, we need to ensure that it serves humanity and not the other way around. But this is an engineering problem—what you could call the control problem. And there is not a lot to say about it, since the technology in question doesn’t exist yet.

I am more interested in what you might call the purpose problem. Assume we maintain control. What if we solved big problems like hunger and disease, and the world kept getting more peaceful: What purpose would humans have then? What challenges would we be inspired to solve?

In this version of the future, our biggest worry is not an attack by rebellious robots, but a lack of purpose.

“What if a happy, healthy life was guaranteed for every child on Earth? How would that change the role parents play?”

I think of this question in terms of my own life. My family gives my life purpose—being a good husband, father, and friend. Like every parent, I want my children to lead happy, healthy, fulfilling lives. But what if such a life was guaranteed for every child on Earth? How would that change the role parents play?

Harari does the best job I have seen of explaining the purpose problem. And he deserves credit for venturing an answer to it. He suggests that finding a new purpose requires us to develop new religion—using the word in a much broader sense than most people do, something like “organizing principles that direct our lives.”

Unfortunately, I wasn’t satisfied by his answer to the purpose question. (To be fair, I haven’t been satisfied by the answers I have seen from other smart thinkers like Ray Kurzweil and Nick Bostrom, or by my own answers either.) In the book’s final section, Harari talks about a religion he calls Dataism, in which the greatest moral good is to increase the flow of information. Dataism “has nothing against human experiences,” he writes. “It just doesn’t think they have intrinsic value.” The problem is that Dataism doesn’t really help organize people’s lives, because it doesn’t account for the fact that people will always have social needs. Even in a world without war or hunger or disease, we would still value helping, interacting with, and caring for each other.

But don’t let a dissatisfying conclusion dissuade you from reading Homo Deus. It is a deeply engaging book with lots of stimulating ideas and not a lot of jargon. It makes you think about the future, which is another way of saying it makes you think about the present. I recommended it to Melinda and she is reading it as I write this review. I can’t wait to talk with her about it over dinner.