No one understands where education is headed better than Sal Khan, and I can't recommend Brave New Words enough.

Growing up in Seattle in the 1960s, I learned very little about the area’s indigenous people. Aside from camping trips my Boy Scout troop would take to a lodge in Chehalis, Washington, where it was at least acknowledged that a tribe had lived on the land, I heard a lot more about the arrival of the first white people in 1851 than about the people who had been here for centuries.

Today the Seattle area and Washington state do a better job of recognizing the role that Native people play in the community and helping them deal with the unique challenges they face. But there is a long way to go.

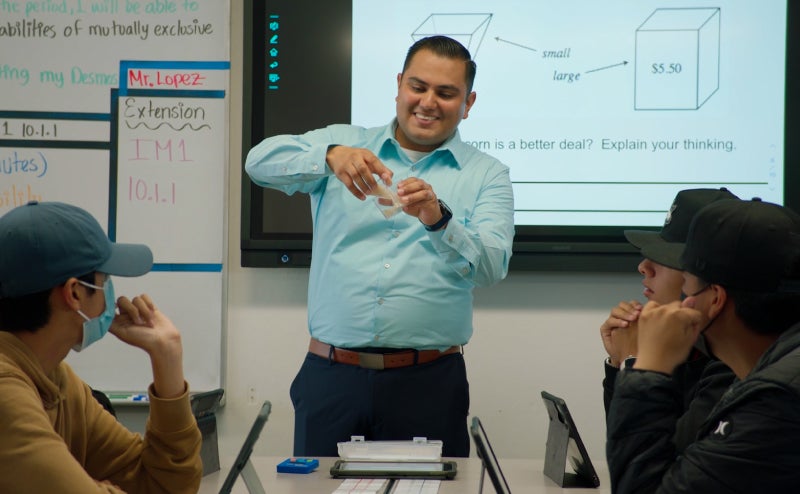

I recently got to learn more about these challenges and how things can get better when I met this year’s Washington State Teacher of the Year. His name is Jerad Koepp, and he runs the Native Student Program in the North Thurston Public Schools, located northeast of Olympia. Remarkably, he’s the first Native educator to receive the award.

Jerad, who is part of the Wukchumni tribe, doesn’t work in just one school. He sees around 200 Native students in 24 different schools across the district, which sits on traditional Nisqually land. In addition to teaching classes on Native history and culture, he travels around the district to meet with Native students. And he offers professional development for teachers and administrators to help them serve the students he works with. “We’re looking at what impacts our student engagement, student retention, and how Native people being represented makes a big difference,” he told me.

It was sobering to hear how badly the typical curriculum underrepresents Native people. “Over 80 percent of school textbooks don’t mention us after 1900,” Jerad told me. And that has a real impact on young people: “If you see yourself being made invisible or misrepresented to other students, that wears you down.” So sometimes his work is as basic as creating opportunities for Native students and their families to come together “and just be who we are for a little bit. Sometimes we talk about culture. Sometimes we just do homework, go over essays, or look at college applications.”

One of the first projects he does with his students is to show them how to make their own deerskin medicine bag, which is used to carry items of cultural importance like cedar, sage, and sweetgrass. The tradition of making them goes back thousands of years. Jerad helped me out as I tried making one myself:

While his students are sewing their bags, Jerad takes the opportunity to explore the deeper meaning behind them. “When we think about medicine,” he said, “we’re thinking conceptually about what we need for our social and emotional wellbeing, and how connecting to culture can help us get through tough times.”

Incredibly, for decades, many states including Washington banned medicine bags in their schools. Although Washington now allows them, Jerad told me that in some other states, items like sacred feathers and beadwork are still confiscated at high school graduation ceremonies. “Just doing something like this,” he said as we sewed up our deerskins, “is pretty revolutionary.”

I asked Jerad about the challenges that Native students face, and I appreciated the nuances in his answer. He acknowledged that traditional risk factors like poverty affect Native students disproportionately—but then he added, “It’s really easy to look at the data with a deficit mindset, rather than seeing all of our Native children as phenomenally asset-based. Because our students participate in incredible things: internships with their tribal governments, canoe journeys, and language programs. All of this comes with knowledge and history that isn’t measured within the Western education system.”

By helping students develop confidence in their identity, he aims to help them do better in school and in life after school, whether that means going to college or joining the workforce. He is also thinking about how to train the next generation of leaders in Native communities. For example, next year he will start teaching a Native Civics class for students who might want to get into tribal government.

I’ve had the pleasure of meeting many of Washington state’s Teachers of the Year, and every time, I think, “I wish we had more teachers like this person.” That is definitely the case with Jerad. I learned a lot from him. He’s a thoughtful leader, and I’m inspired by his commitment to helping Native students embrace their culture and make the most of their talents.