I was honored to be one of the speakers at the Leaders Summit on Climate hosted by President Biden.

The car I drive to work is made of around 2,600 pounds of steel, 800 pounds of plastic, and 400 pounds of light metal alloys. The trip from my house to the office is roughly four miles long, all surface streets, which means I travel over some 15,000 tons of concrete each morning.

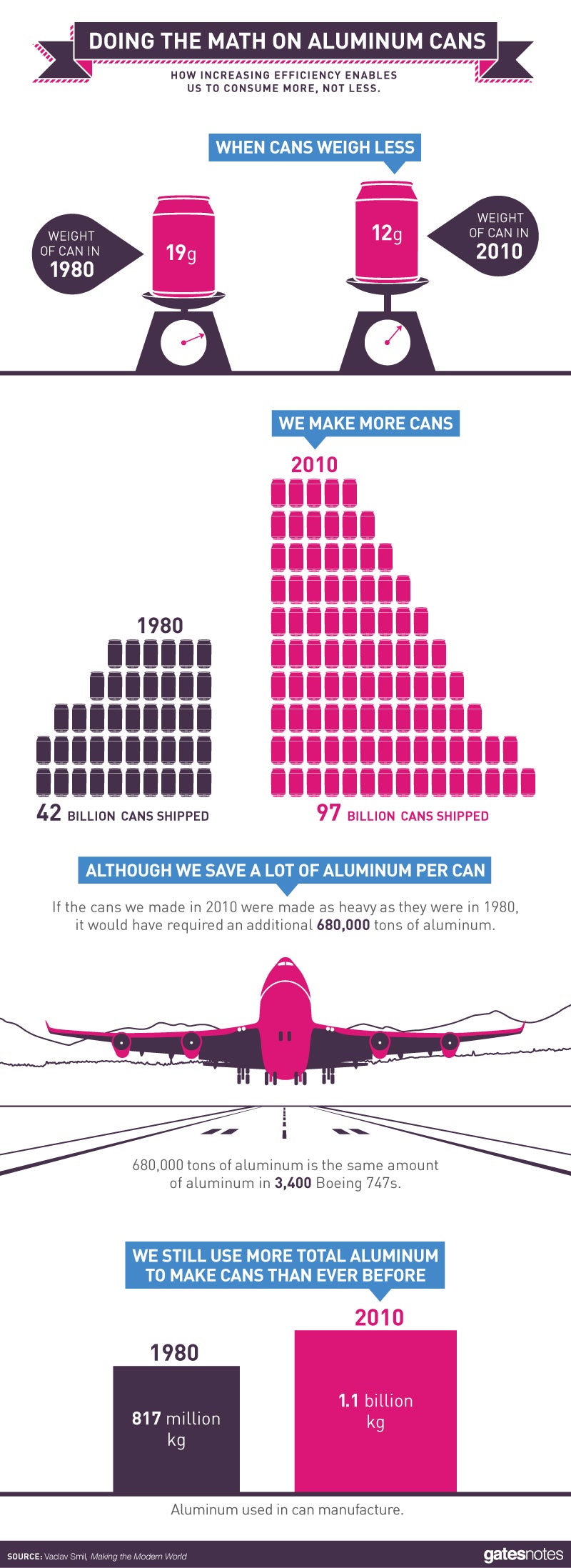

Once I’m at the office, I usually open a can of Diet Coke. Over the course of the day I might drink three or four. All those cans also add up to something like 35 pounds of aluminum a year.

I got to thinking about all this after reading Making the Modern World: Materials and Dematerialization, by my favorite author, the historian Vaclav Smil. Not only did I learn some mind-blowing facts, but I also gained a new appreciation for all the materials that make modern life possible.

This isn’t just idle curiosity. It might seem mundane, but the issue of materials—how much we use and how much we need—is key to helping the world’s poorest people improve their lives. Think of the amazing increase in quality of life that we saw in the United States and other rich countries in the past 100 years. We want most of that miracle to take place for all of humanity over the next 50 years. As more people join the global middle class, they will need affordable clean energy. They will want to eat more meat. And they will need more materials: steel to make cars and refrigerators; concrete for roads and runways; copper wiring for telecommunications.

I had already read Smil’s books on energy and diet. Smil says at the start of Making the Modern World that he won’t spend much time on those topics (which means climate change doesn’t come up much). Instead he’s interested in the materials we use to meet the demands of modern life. Can we make enough steel for all those cars and enough concrete for all those roads? What are the risks if we do? In other words, can we bring billions of people out of poverty without destroying the environment?

Smil excels at answering big questions like these. Although he doesn’t make many predictions, he does something that’s even more valuable: He explains the past. He helps you understand how we got where we are, which tells you something about where we’re going. I study Smil’s histories so I can understand the future.

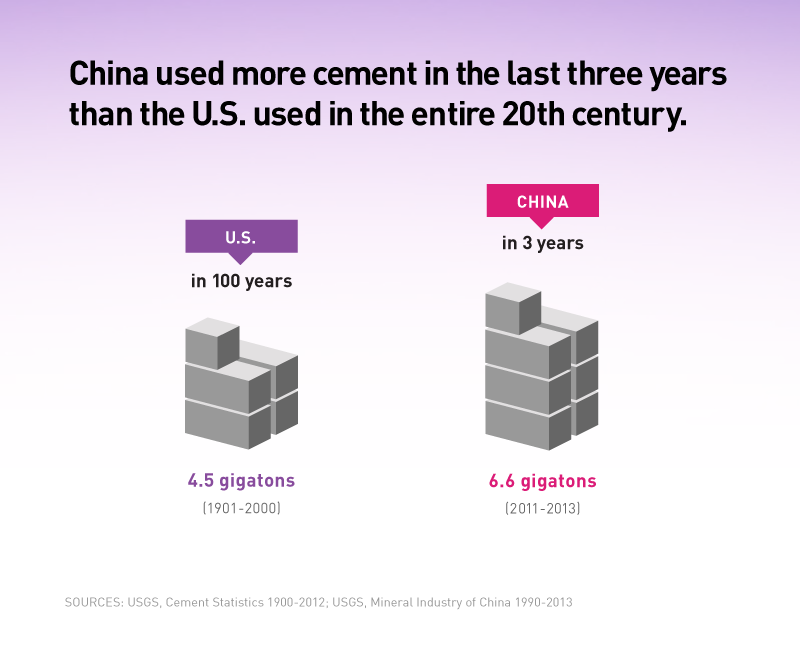

He argues that the most important man-made material is concrete, both in terms of the amount we produce each year and the total mass we’ve laid down. Concrete is the foundation (literally) for the massive expansion of urban areas of the past several decades, which has been a big factor in cutting the rate of extreme poverty in half since 1990. In 1950, the world made roughly as much steel as cement (a key ingredient in concrete); by 2010, steel production had grown by a factor of 8, but cement had gone up by a factor of 25. This animated GIF shows the dramatic transformation of Shanghai since 1987. Most of what you’re seeing in that picture is concrete, steel, and glass.

You can also see the importance of concrete in the graphic below, which illustrates what Smil calls the most staggering statistic in his book:

One material that I have a personal interest in is paper (which comes in a distant third in terms of annual production, behind cement and steel). I’ve been saying for many years that widespread computing would eliminate the need for paper, so I was curious to see where Smil thinks things stand. According to his research, paper production started dropping in the United States in the mid-90s and in Japan a few years later. But global consumption is still going up, driven by China and other growing Asian countries. In 2011 China alone accounted for just over 25 percent of the global paper supply. It was also the world’s top importer of waste paper for recycling. The odds are decent that the junk mail you tossed into the recycling bin last night is headed for China.

I still think we’ll see a paperless office someday, given the downward trend in the United States and elsewhere and the rise of ubiquitous computing. But Smil reminded me that the death of paper is a long way off. This is another reason I like to read him—he keeps my optimism from getting out of hand.

After reviewing the trends, Smil introduces a surprising and counterintuitive idea he calls relative dematerialization. As innovation lets us make a given product more efficiently, with fewer materials or energy, prices go down and consumption goes up. Someone figures out how to make cell phones with less metal, which makes them cheaper, which makes them more widespread. Less metal per phone, but more phones, so more metal overall. “Less,” he writes, “has thus been an enabling agent of more.”

Here’s how the idea applies to soda cans:

What does all this tell us about the future?

First, the good news: Thanks to technical advances, we can make major industrial products like steel and cement more efficiently than ever. On average, making a ton of steel today takes a third as much energy as it did in 1950, and produces 10 percent less carbon.

On the other hand—getting back to relative dematerialization—there’s no end in sight to the rising demand for more materials. Even though the richest countries are leveling off, many other countries are catching up. Smil points out that if the poorest 80 percent of the planet reaches a living standard that’s just a third of what people in rich countries enjoy, the world should expect to continue using more materials for generations to come.

So if consumption won’t level off anytime soon, are we doomed to run out of the stuff that makes modern life possible? As usual, Smil refuses to provide pat predictions. He does say we shouldn’t lose sleep worrying about running out in the next 50 years. Beyond that, there are a lot of variables, but we might need to limit the use of some materials or do a better job with recycling. Smil nods to several innovations that could help avoid future shortages, such as new materials that could cut our need for cement by 65 percent.

I agree with Smil that humans have an amazing capacity for finding ways around scarcity by using materials more efficiently, recycling them, or finding substitutes. The big concern isn’t so much whether we will run out of anything—it’s the impact that extracting and using these materials is having on the planet. For example, the cement industry now accounts for about 5 percent of all carbon-dioxide emissions. That’s one reason I think that developing affordable energy that produces zero carbon is one of the most important things we can do to lift people out of poverty.

I’m also surprised that the oceans get so little attention compared with other environmental problems, and I think they deserve more. They are being overfished and the waters are turning more acidic, killing off coral reefs around the world. Smil cites estimates that at least 6.4 million tons of plastic litter enter the oceans every year. We may have already done irreparable damage to these precious resources.

Above all, I love to read Smil because he resists hype. He’s an original thinker who never gives simple answers to complex questions. He gives me a lot to think about on my drive to work, before my first Diet Coke of the day.