A person that I admire as well as like—that’s the perfect description of how I feel about Warren.

So far, I’ve participated in 11 virtual events to discuss my new book, How to Avoid a Climate Disaster, with a few more to come. At each one, I’ve talked about how the world needs to transform its entire physical economy so we can stop emitting greenhouse gases by 2050, and at nearly every event, I’ve been asked some version of this question: “What about the people who will lose jobs in this transition?”

It’s a great question. People are right to be concerned about it. Unfortunately, the way we talk about this issue can be polarizing, and the arguments end up falling into one of two extreme camps.

For those who are worried about climate change, it’s easy to dismiss anyone who calls out lost jobs in the fossil-fuel industry as a climate denier. And for those who are worried about losing jobs, it’s easy to conclude that environmentalists don’t understand the impact this transition will have on workers, their families, and their communities.

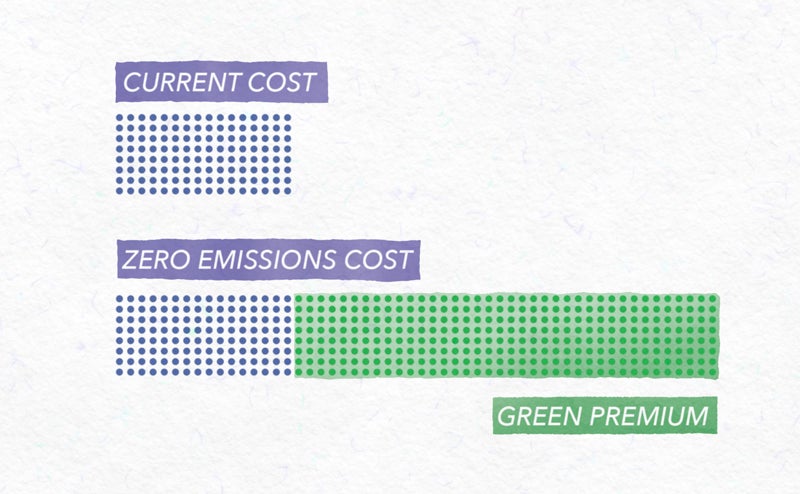

The truth is, everyone has legitimate concerns here. The world does need to transition to a zero-carbon economy over the next 30 years. Yet it’s also true that many communities rely on an economic engine—like oil refineries—that’s powered by fossil fuels. If the only job you’ve ever had relies on fossil fuels, it must be gut-wrenching to imagine it going away. Knowing that the transition is necessary to avoid a climate disaster doesn’t make it any easier.

So I want to share some thoughts about how to strike the right balance.

To begin with, it’s crucial to recognize that this transition will happen in an economy that is already incredibly dynamic. The demand for workers can shift quickly from one sector to another, and from one geographic area to another. And these changes aren’t just driven by clean energy—other factors like automation and robotics play an essential role too.

By and large, this dynamism is good for the economy. I think that’s going to be true in the clean-energy transition too, because it will create so many new opportunities for workers. In some cases, their skills will transfer directly. For example, if green hydrogen fuels turn out to be a big business, we’ll still need pipelines and trucks to move them around—just as we move around oil and gas today. Mining skills could also be useful in sourcing minerals, like lithium and copper, that are used in the production of clean technologies and will be in increasingly high demand.

There will also be jobs involved in constructing and running all the infrastructure for the green economy: wind and solar farms, modernized power grids, battery factories, refineries for sustainable fuels, facilities for long-duration storage of electricity, direct-air capture facilities, and more.

But you don’t have to be a climate skeptic to see the challenges with all this. These new, clean solutions may not use the same workforce or be located in the same regions as their conventional counterparts. (Most of America’s wind power is in the middle of the continent, not in coal country.) Some new jobs may not be as good as the ones that are lost. And some new technologies may need fewer workers than the ones they’re replacing.

For example, electric vehicles need less maintenance because they have fewer moving parts than cars with internal combustion engines. In a future with lots of EVs on the road, fewer people will be needed to repair them and to work at gas stations. Whether the shift to EVs ends up being good or bad for America’s automotive industry will depend on whether governments act now to encourage manufacturing—in existing and new plants alike—throughout the entire supply chain, from parts to assembly.

Over time, dozens of industries will go through their own evolutions as they reduce and eliminate their emissions. Workers and communities across the country will be affected: coal miners in West Virginia, factory workers in Ohio and North Carolina, automakers in Detroit, cement makers in Seattle. And it’s not just in the United States—the same changes will affect workers around the world.

What can be done about it?

Unfortunately, there’s no single solution that will work in every industry or every community. The federal government can provide guidance and funding, help connect regions that are facing common challenges, and create incentives to make good clean-energy jobs accessible to everyone. But in the end, it’s really state and local leaders—from the public and private sectors, labor groups, and community groups—who will be crucial.

There are four principles that should guide the transition:

Think big and start now. The deadly power outages in Texas are a painful reminder that unpredictable weather is going to be more common, and there’ll be times when it affects the ability of entire regions of the country to function effectively. Governments should invest now in upgrades to make the power grid and all U.S. infrastructure more resilient. That process is an example of how this transition can make the country better prepared to prevent a climate disaster while significantly increasing opportunities for good jobs.

The sooner this transition starts, the better off everyone will be. New technologies like clean cement and sustainable aviation fuel will need manufacturing facilities, supply chains, and distribution networks—all of which will employ many people in construction and operations. Whoever builds the first of these will have a leg up on building the next ones, and whoever figures out the operations side first will able to scale faster than their competitors. Each of these pieces of infrastructure should be thought of as large construction projects requiring a significant amount of labor. They’ll also be long-term investments—these plants and refineries will remain in these communities for decades.

There’s also tremendous economic opportunity in research and development funding. R&D money creates immediate jobs in the communities where it’s spent, and it also gives them a head start on growth—since the places where that money is invested are often the places where new companies take root. Meanwhile, the federal government can adopt policies that encourage innovators to demonstrate and deploy their new ideas in the communities where they discover them.

In choosing where to make these investments, equity needs to be a driving factor. Polluting industries are disproportionately located in communities of color, to the detriment of their health and well-being. And these communities tend to be more economically vulnerable and have fewer safeguards, so they will often be hit harder than others. In the transition to clean energy, people in disadvantaged communities deserve opportunities for good jobs that won’t put their health or the environment at risk.

Learn from promising examples. Toledo, Ohio, has been a hub for the glass-making industry for so long that its nickname is “the Glass City.” After its manufacturing base hit hard times, local leaders identified a new area where the city’s glass roots were especially relevant: making solar panels. This work has become a key part of the local economy.

In Pueblo, Colorado, business and government leaders are transforming a historic iron mill—once the only steel-making company west of the Mississippi—into the world’s first electric arc furnace powered primarily by solar energy. That project will ensure that at least 1,000 steelworkers keep their jobs and create hundreds of construction jobs.

And in New York state, all offshore wind projects are now required to pay prevailing wages to the workers who are installing wind turbines. Local unions played a crucial role in pushing for the agreement.

Commit the resources to make it work. Making sure the transition is just and fair won’t be cheap. Germany, for example, is planning to spend more on this than on research and development into clean-energy innovation.

But it’s not simply about spending more. If it wants to compete with Europe and China in the green economy, the U.S. will need a generation of engineers and scientists who focus on these new areas—so the energy transition is another compelling argument for improving America’s education system. Even relatively small improvements in schools would help graduates be more adaptable as they move from one job or career to another.

Innovators at universities also need to be connected with entrepreneurs and investors so their ideas can get from the lab into the market—which will spark the creation of new companies that create jobs and opportunity. The University of Toledo, for example, has been an important partner in the transition that city has undergone.

Stay on track. Nearly every political party in Europe is committed to avoiding a climate disaster. So when they make 10- or 20-year commitments to funding innovation or building infrastructure, the private sector can take them seriously. But in the U.S., when there’s a change in leadership in Congress or the White House, it can mean that priorities and policies change too—which makes it hard for companies to raise the capital for, say, retooling steel and cement factories. A serious long-term commitment to fighting climate change by all leaders would make a big difference.

Moving to a green economy is the biggest challenge the world has ever faced. I’m optimistic we can do it, for all the reasons I explain in my book. But it needs to benefit everyone—including those workers and communities who depend on the fossil fuels that we need to get rid of.